I

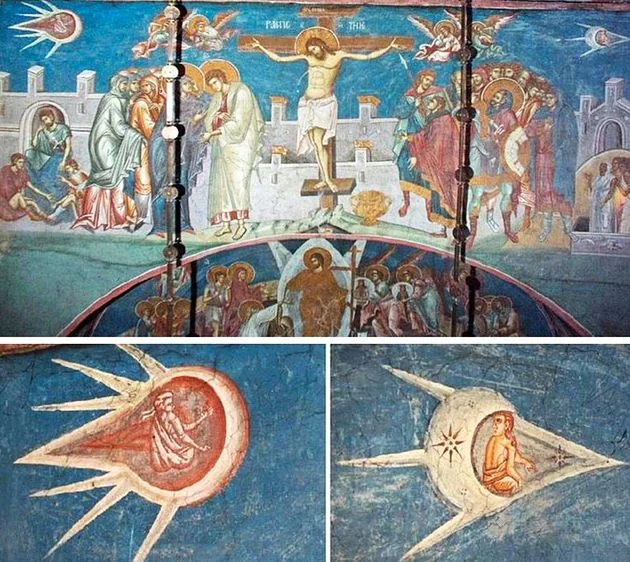

A monk at Visoki Decani Monastery in 1457

Young novitiate Nicodemus stands in the apse

of an achingly beautiful church,

constructed by artisans over half a medieval lifetime,

painted by workers embedding the glory of Christ in its walls.

But Nicodemus is not awed by the incarnation, or

the gilded haloes, or

the iconographic miracles.

Instead, he gazes each day at

two small, nearly incomprehensible painted figures,

two strange images flanked by woeful angels and lamenting heralds.

One a fiery red sun, spiky and brilliant rays retreating toward the left as — a man, he is sure of it — sits calmly in it as it careens.

The other a moon like an apple if it were an oxcart, also a man inside at the reins.

Both flying among the stars in the black firmament of night.

O! For a way to channel the swiftness of a sparrow higher than the sun.

What they must see.

What glories they must witness from on high

If ever humans could take to the sky like starlings at night.

II

A sailor on the HMS Erebus in 1847

At the frozen tip of the world, two creaking, splintering ships sit stone-cold like sentinels, unmoving in pack ice that stretches for miles

They have not sailed in more than a year — the summer thaw that promised salvation and westward travel simply

did

not

come.

What world is this, Assistant Surgeon’s Mate Henry thinks, that the laws of nature and man suspend at will?

His world, by parts, is tending to rum-soaked, busted lips from drunken brawls,

soothing forgotten, frostbitten fingers that escaped woolen gloves and turned black as soot.

His world is two lonely ships,

two damp, suffocating tenements filled with the scents of boiled salt pork, fifty mens’ flatulence, and stale pipe smoke.

The first time the Northern Lights appear, Henry steps outside to see.

There is white the color of a billion brilliant stars,

there is the ever-present darkness that cannot be measured,

and there are now green waves of otherworldly light that reverberate across the ice-caked masts and lines.

For a moment, he imagines they are being ripped

free of the shackles of of pack ice,

the only ships manned by His Majesty’s Navy to escape

gravity and sink up into the night sky.

They travel home to England by — and through — the stars,

a navy navigating the blotchy white sea of the Milky Way

the long way round.

III

Michael Collins looking at the lunar lander in 1969

To take it all in at a single glance:

the Earth,

and the moon,

and Buzz

and Neil.

Every single person, every single place, every single thing he had ever known for 38 years of being alive,

opposite him as he orbits the moon alone.

21 hours he spends up orbiting in the command module,

Buzz and Neil below

planting flags and feet

on the earth’s satellite,

never more than a few safe steps from the lunar lander.

For a part of each orbit, he and the ship disappear

behind the dark of the moon — 300,000 kilometers and absolutely no

radio reception separating

him

from

all of humanity.

For this solitary venture, the press would crown him “the loneliest man in history.”

Alone, but not lonely,

several meals alone at the wheel,

no one to share rehydrated turkey & gravy and

sweaty processed cheese cubes,

no one to share the

view from the

otherside of the moon.

But he didn’t have time to dwell, his eyes fixed intently upon the lander and his friends gamboling in the moondust below for as long as he could.

And when they disappeared from view, he thought only of

seeing them together again soon,

returning to the command module triumphant in exploration,

the smell of space following them in like burning steak

in the

cockpit.

Best not to dwell if something bad were to happen.

Best not to dwell.

IV

A farmbot working on a generation ship in 2148

DEM1-TR (demeter) is the constant gardener

on board the Dauntless.

Eight generations have come to know her

and her dirt-caked, servo-driven mechanical fingers,

her encyclopedic knowledge of how to grow butter lettuce in hydroponics

and how to coax the tallest stalks of corn from the soil

Eight generations have marveled at

her strangely joyful commitment to

harvesting human-waste for fertilizer

(it works).

Demeter knows that cherry tomatoes, when left to ripen on the vine,

make the crew a little happier when sent upstairs,

And though she cannot taste them,

Demeter knows that offering a tomato right then and there in the field

— no cooking, no washing —

makes the humans smile.

It is her programming, and

this programming does not stop when,

slowly,

then suddenly,

consumption of wheat and kale and potatoes

ends.

The virus that could not be contained spreads

and spreads —

she has no off-switch,

never had a single programming on what to do if humans

disappeared.

So she still

tills,

plants,

waters,

harvests.

A perpetual gardener, tending a generation ship’s foodstuffs

until her servers wear out.

The ship, full of produce and grains and greens,

takes a tour of the galaxy.

Leave a Reply